New Theory Illustrates The Development Of The Universe May Be Different Than We Thought

The history of the universe is predicated on the idea that, compared to today, the universe was hotter and more symmetric in its early phase. Scientists have thought this because of the Higgs Boson finding—the particle that gives mass to all other fundamental particles. The concept is that as one analyzes time back toward the Big Bang, the universe gets hotter and the Higgs phase changes to one where everything became massless. Now, physicists are presenting a new theory that suggests an alternative history of the universe is possible. The research, funded in part by the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy, is led by Patrick Meade, Ph.D., Associate Professor in the C.N. Yang Institute for Theoretical Physics at Stony Brook University and his former Ph.D. student, Harikrishnan Ramani. The findings are published in the latest edition of Physical Review Letters.

The researchers propose a theory beyond the Standard Model of particle physics that describes how electroweak symmetry is not restored at high temperatures. If correct, this would lead to many potential consequences during the development of the universe, such as other phases of matter, particles staying massive in primordial plasma, and new possibilities for explaining the matter-antimatter asymmetry. The theory also highlights how the history of the universe could be very counter-intuitive compared to many phenomenon on earth that demonstrate symmetry restoration.

Magnetic-field cameras: mapping a path to optimal MRI performance

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become a mainstay of medical imaging facilities. Superior soft-tissue contrast versus CT scans and the use of non-ionizing radio waves to visualize a rich matrix of functional information – including blood volume/oxygenation and localized metabolic activity within tumour sites – represent a winning combination for clinicians in the diagnosis and treatment of all manner of diseases.

Underpinning that clinical capability is an array of enabling technologies, the largest and most expensive of which is the cryogenically cooled superconducting magnet that sits at the heart of today’s cutting-edge MRI scanners. Clinical MRI machines typically have a magnetic-field strength in the range 0.1 to 3.0 T – though research systems for human and small-animal applications are available at much higher fields (up to 25 T). In every case, these multimillion-dollar systems require a magnetic field that combines extreme stability with extreme uniformity (to within a few ppm) to ensure optimal imaging performance.

To service that need, Swiss manufacturer Metrolab Technology SA, a market-leader in precision magnetometers, has developed a portfolio of measurement tools and accessories to enable MRI equipment manufacturers to quantify and map the magnetic subsystems at the heart of their clinical MRI scanners. Metrolab’s products are used by MRI equipment vendors throughout the technology and innovation cycle: to support R&D on next-generation systems; in the production and assembly plant; and during the installation of new MRI machines in clinical facilities.

“The biggest application – in terms of the volume of test units we ship – is for the installation and commissioning of new MRI scanners in hospitals and clinics all over the world,” explains Philip Keller, marketing and product manager at Metrolab.

Magnetic iterations

The core product in Metrolab’s portfolio is the NMR magnetic-field camera, the latest iteration of which – the MFC2046 – provides magnetic-field measurements with a resolution of 10 ppb; overall positioning tolerances well under 1 mm; and a measurement range from 0.2 to more than 25 T (versus a 7 T limit with the previous-generation system). The camera comes with a MFC9046 probe array, a unit with up to 255 measurement points that generates detailed field maps inside the MRI magnet bore in roughly five minutes.

“With our new-generation MFC2046 camera system, we’re also optionally combining the functionalities of our single-point, wide-range magnetic probe into the probe array,” says Keller. “The former is used for magnet ‘ramping’, while the probe array offers detailed field mapping – a combination that saves MRI manufacturers time and money in the assembly plant and during MRI system installation in the clinic. It’s a win-win because technicians no longer need to swap out two test instruments to perform these different sets of measurements.”

Consider a typical installation scenario in which a new MRI machine is shipped to a clinical customer. For safety reasons, the magnet is usually dispatched from the factory without any magnetic field, ahead of installation in a magnetically and electrically shielded room at the customer site. At this point, the next task for the manufacturer’s technician team is to bring the MRI scanner’s magnetic field up to the specified operating level by injecting current into the magnet’s superconducting coils.

“The wide-range probe [in the MFC9046 probe array] is used to track this ramping process from zero to say 1.5 or 3.0 T,” explains Keller. “Then, as the magnet nears the desired field level, this high-precision single-point probe enables the technicians to get the field setting just right.”

Installation of the MRI magnet continues with an iterative, fine-tuning process known as shimming. The aim here is to make the magnetic field inside the bore of the MRI scanner more homogeneous by placing pieces of iron (shims) in the appropriate place or by adjusting the current in special shim coils. “The technicians must first ramp the magnet to its nominal field, followed by detailed field mapping and the shim adjustments,” says Keller. “They then have to remap the magnetic field to make sure the shimming has had the desired effect in terms of field homogeneity.”

Think small

As well as applications in whole-body MRI, Metrolab’s magnetic-field camera and probe arrays are also suitable for use with smaller-scale MRI systems with magnet bores as small as 40 mm. Small-bore MRI scanners are used by drug companies to image a range of animal subjects – mice, rats and guinea pigs, for example – in drug evaluation trials. These test animals serve as “human models” that allow scientists, through repeat MRI scans, to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy (as well as secondary side-effects) of new drug regimes over time. Elsewhere, small-bore MRI systems find niche applications in sports medicine – and specifically the imaging of extremity injuries to knees, elbows and ankles.

In the past, Metrolab served this specialist instrumentation market with its single-point NMR probe. To generate a map of the magnetic field, a technician had to position the probe at hundred of points within the magnet bore – a process that took several hours. Now, with the MFC9046 multiprobe array, it’s possible to generate the same field map in around five minutes. “The compressed data acquisition time represents a significant gain from a production and installation perspective,” claims Keller. It also provides better positional accuracy and minimizes inconsistencies due to magnet drift.

Measurement speed aside, one of the main engineering challenges when mapping a small-scale MRI system is the size of the magnet bore. “With our new MFC9046 system we use a pulse-waved NMR measurement technique instead of continuous-wave,” notes Keller. “That means we can have the electronics remote from the probe head and in turn make the probe array a lot smaller versus our previous-generation unit.”

Another key requirement – given that the output is a map of magnetic field inside the small MRI magnet bore – is the positioning accuracy of the field measurements. “You need to have accurate magnetic-field measurements, but you also need to have accurate positions in geometric space,” explains Keller. “As you rotate the probe array inside the magnet bore, the mechanical accuracy of the positioner has to be spot on, with sub-mm tolerances.”

To extend its coverage of the small-scale MR market, Metrolab has also developed a new miniature probe array (MFC9146) for field-mapping of NMR spectroscopy systems used in materials science and applied chemistry laboratories.

First exoplanet found around a Sun-like star

Anyone over the age of 35 will remember growing up in a world in which only one planetary system was known — our own. We remember proudly reciting the names of the nine planets (eight before Pluto’s discovery in 1930, and again today with its reclassification as a dwarf planet in 2006) and wondering what other planets might exist around the stars in the night sky. Contemplating life beyond the Solar System was relegated to science fiction. This all changed in 1995 when Mayor and Queloz reported the detection of the first exoplanet around a Sun-like star.

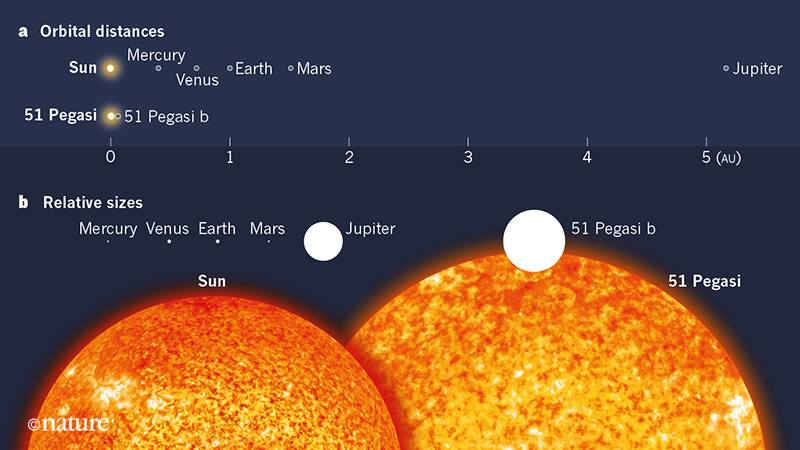

The discovery of the gas-giant planet — named 51 Pegasi b after its parent star, 51 Pegasi — came as a surprise. Gas-giant planets, such as Jupiter, are located in the outer parts of the Solar System. The prevailing theory was, and still is, that the formation of these planets requires icy building blocks that are available only in cold regions far away from stars. Yet Mayor and Queloz found 51 Pegasi b to be orbiting about ten times closer to its host star than Mercury is to the Sun (Fig. 1). One possible explanation is that the planet formed farther out and then migrated to its current location.

The gas-giant planet was not the first exoplanet to be discovered. However, the previous detections were of even stranger objects orbiting pulsars — rapidly spinning neutron stars, which are the collapsed remnants of hot massive stars. The discovery of 51 Pegasi b was the first to substantiate the existence of planets around long-lived hydrogen-burning stars that resemble the Sun.

The bizarre character of a gas-giant planet orbiting so close to its parent star engendered considerable scepticism about the true nature of 51 Pegasi b. Mayor and Queloz detected the planet through minute back-and-forth motion of 51 Pegasi, which seemed to indicate that a planet-mass object was pulling on the star. But this stellar motion, sensed by frequency shifts in the spectra of light from 51 Pegasi, had other possible interpretations. A lively debate ensued in the literature about whether pulsations of the star might be masquerading as a planetary signature.

This debate was put to rest in 1998 when the astronomer David F. Gray wrote a paper refuting his previous assertion that the stellar spectra were indicative of pulsations rather than a planet. Further vindication came through the detection of planets similar to 51 Pegasi b, as other researchers combed their existing data for similarly unexpected planetary signals. These highly irradiated giant planets have come to be known as hot Jupiters.

In the 24 years since the discovery of 51 Pegasi b, about 4,000 exoplanets have been identified. Other detection techniques have entered the scene, including the transit method, in which an exoplanet is revealed through the subtle dimming of its host star as the planet crosses the line of sight between Earth and the star. Hot Jupiters have continued to be discovered by the many exoplanet searches that are sensitive to large planets on close orbits. However, it is now known that such objects are intrinsically rare, orbiting only about 1% of Sun-like stars.

By contrast, planets known as super-Earths and mini-Neptunes abound. Such objects, which inhabit the size and mass gap between the rocky and gas-giant planets of the Solar System, were also a surprise to planet hunters, but seem to be commonplace in our Galaxy. There is now good reason to think that the Milky Way contains more planets than it does stars.

Mayor and Queloz’s detection of 51 Pegasi b gave rise to a new field of astronomy. The ranks of exoplanet researchers have been steadily growing, by some counts now making up about one-quarter of the astronomy profession. Incipient subfields include the study of exoplanet demographics and the characterization of exoplanetary atmospheres.

This characterization has confirmed that hot Jupiters truly are gas-giant planets, but ones representing what our own Jupiter would look like if it were suddenly transported 100 times closer to the Sun. Amid the scorching-hot hydrogen–helium envelopes of these planets, astronomers have detected trace amounts of steam, carbon monoxide and metal vapors. Such atmospheric studies could lead to the eventual characterization of exoplanets that resemble Earth.

The future of the exoplanet field is bright. In April 2018, NASA launched the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), a space telescope that is just beginning to fulfil its mission of finding small transiting planets around the brightest stars in the night sky. These planets will be ideally suited for follow-up using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), once it launches, to measure their atmospheric properties and compositions. Following on the heels of JWST, the European Space Agency has selected the Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey (ARIEL) space telescope to launch in 2028. ARIEL will be dedicated to characterizing the atmospheres of a wide sample of exoplanets.

These programmes are paving the way towards the ultimate goal of potentially detecting the signatures of life on an exoplanet. This goal could most optimistically be achievable in the next decade, but more realistically will require a new generation of space- and ground-based telescopes. What is remarkable is that humans have gone from discovering the first exoplanets to legitimately plotting out the search for life on these worlds in just a quarter of a century.